Evolution

Evolution

Intelligent Design

Intelligent Design

Life Sciences

Life Sciences

Eric Davidson (1937-2015) on Gene Regulatory Networks

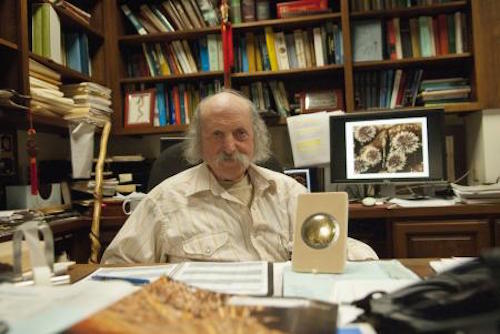

With the passing of paleontologist David Raup and biologist and science historian Will Provine in recent months, we’ve been given the opportunity to reflect on two famous evolutionary scientists who were brave enough to critique neo-Darwinism. But there’s another one we’ve missed — Eric Davidson, the developmental biologist from Caltech who, sadly, passed away this past August.

Davidson is famous for formulating the concept of developmental gene regulatory networks (dGRNs), a description of how genes interact with one another to regulate their expression in the early stages of development. The activity of a dGRN is very influential in determining the body plan of an animal.

Recently, an email correspondent contacted me to ask about dGRNs. This person had been in communication with an evolutionary biologist who claimed that dGRNs are very flexible and could show how new animals evolved. I didn’t know Eric Davidson so I can’t share any personal anecdotes, but it seems like an appropriate time to review what the great dGRN expert Eric Davidson said on this point.

As Stephen Meyer explains in Darwin’s Doubt, Davidson believed, based upon his experimental work, that dGRNs aren’t very flexible at all. Davidson observed that mutations affecting the dGRNs that regulate body-plan development lead to “catastrophic loss of the body part or loss of viability altogether.”1 He explained:

There is always an observable consequence if a dGRN subcircuit is interrupted. Since these consequences are always catastrophically bad, flexibility is minimal, and since the subcircuits are all interconnected, the whole network partakes of the quality that there is only one way for things to work. And indeed the embryos of each species develop in only one way.

He further wrote:

Interference with expression of any [multiply linked dGRNs] by mutation or experimental manipulation has severe effects on the phase of development that they initiate. This accentuates the selective conservation of the whole subcircuit, on pain of developmental catastrophe…”2

But perhaps most strikingly, Davidson, in discussing hypothetical “flexible” dGRNs, acknowledged that we are speculating “where no modern dGRN provides a model” since they “must have differed in fundamental respects from those now being unraveled in our laboratories.”1

Meyer cited much of this evidence in Darwin’s Doubt. Now consider how UC Berkeley paleontologist Charles Marshall responded to Stephen Meyer when Marshall reviewed Meyer’s book in the journal Science.

Marshall wrote: “Today’s GRNs have been overlain with half a billion years of evolutionary innovation (which accounts for their resistance to modification), whereas GRNs at the time of the emergence of the phyla were not so encumbered.”3

The only reason Marshall would have said this is if modern dGRNs are in fact “so encumbered” that they could not provide a model for evolution. Marshall was forced to ignore modern experimental data and speculate that perhaps in the past dGRNs were different.

Thus, while Marshall’s title, “When Prior Belief Trumps Scholarship,” was an accusation aimed against Meyer’s work, I think that it’s far more apt to turn that right around at Marshall’s own arguments, as Meyer explained in his response to Marshall.

As a result of all of this, Davidson concluded that, “contrary to classical evolution theory, the processes that drive the small changes observed as species diverge cannot be taken as models for the evolution of the body plans of animals.”4 He elaborated:

Neo-Darwinian evolution … assumes that all process works the same way, so that evolution of enzymes or flower colors can be used as current proxies for study of evolution of the body plan. It erroneously assumes that change in protein- coding sequence is the basic cause of change in developmental program; and it erroneously assumes that evolutionary change in body- plan morphology occurs by a continuous process. All of these assumptions are basically counterfactual. This cannot be surprising, since the neo-Darwinian synthesis from which these ideas stem was a premolecular biology concoction focused on population genetics and . . . natural history, neither of which have any direct mechanistic import for the genomic regulatory systems that drive embryonic development of the body plan.1

The bottom line is that experimental research on dGRNs in modern animals shows that they do NOT appear flexible. Experts acknowledge this. They even acknowledge that it poses a challenge to neo-Darwinism. Those who claim otherwise are simply mistaken.

References:

(1) Eric Davidson, “Evolutionary Bioscience as Regulatory Systems Biology.” Developmental Biology, 357:35-40 (2011).

(2) Eric H. Davidson and Douglas Erwin. “An Integrated View of Precambrian Eumetazoan Evolution.” Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology, 74: 1-16 (2010).

(3) Charles R. Marshall, “When Prior Belief Trumps Scholarship,” Science, 341 (September 20, 2013): 1344.

(4) Eric Davidson, The Regulatory Genome: Gene Regulatory Networks in Development and Evolution. Burlington: Elsevier, 2006, p. 195.

Image: Eric H. Davidson via Caltech.