Evolution

Evolution

Free Speech

Free Speech

Intelligent Design

Intelligent Design

Ten Myths About Dover: #4, "The Dover Ruling Refuted Intelligent Design"

Editor’s note: The Kitzmiller v. Dover decision has been the subject of much media attention and many misinterpretations from pro-Darwin lobby groups. With the tenth anniversary of Kitzmiller approaching on December 20, Evolution News offers a series of ten articles debunking common myths about the case. Look here for Myths 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10.

On the opening day of the 2005 Dover trial, the plaintiffs’ leadoff expert witness, noted anti-ID biologist Kenneth Miller, was asked, “Are you able to give us some examples of how modern genetics has applied to evolutionary theory?” His Exhibit A argument was to testify that the human beta-globin pseudogene is “broken” because “it has a series of molecular errors that render the gene non-functional.” Since humans, chimpanzees, and gorillas share “matching mistakes” in the pseudogene, he told the court, this “leads us to just one conclusion … that these three species share a common ancestor.”

However, Miller’s assertion, crucial to his testimony, is now known to be wrong. A 2013 study in Genome Biology and Evolution reported that the beta-globin pseudogene is functional.

Humans have six copies of the beta-globin gene. Five produce beta-globin proteins, but the sixth, the pseudogene copy, has a premature stop codon that prevents translation. The researchers compared all six genes across humans and chimpanzees, and found the beta-globin pseudogene exhibits fewer differences than would be expected if it were non-functional and accumulating random mutations at a constant rate. This “conserved” sequence between the pseudogene and the functional versions of the gene suggests the beta-globin pseudogene has a selectable function, making it less tolerant of mutations. The researchers argue that the pseudogene works as an on/off switch, regulating expression of protein-coding beta-globin genes during embryonic development.

Of course Miller, testifying in 2005, cannot be faulted for not citing a paper published in 2013. But the lesson here is this: science is always making new discoveries, and court cases cannot settle scientific disputes. Unfortunately, Judge Jones took the plaintiffs’ testimony as the final truth on evolutionary science, and ignored the fact that even in 2005 many of the scientific claims in his ruling were strongly challenged by the evidence.

Misstating Irreducible Complexity

During the trial, pro-ID expert witnesses like biochemist Michael Behe and microbiologist Scott Minnich both testified about how irreducible complexity makes a positive case for design. Judge Jones ignored this testimony and twisted irreducible complexity into what he called an “illogical contrived dualism” which argues for design strictly by negating Darwinian evolution:

[T]he argument of irreducible complexity, central to ID, employs the same flawed and illogical contrived dualism that doomed creation science in the 1980’s … Irreducible complexity is a negative argument against evolution, not proof of design .. Irreducible complexity additionally fails to make a positive scientific case for ID.

As a description of how irreducible complexity works and how we argue for design, this is absolutely wrong. The argument for design is a positive one. Intelligent design is not simply an argument against evolution. As explained in a scientific paper by Minnich and Stephen Meyer that was documented to Judge Jones, whenever we know the origin of an irreducibly complex system, it always traced back to an intelligent mind:

Molecular machines display a key signature or hallmark of design, namely, irreducible complexity. In all irreducibly complex systems in which the cause of the system is known by experience or observation, intelligent design or engineering played a role in the origin of the system. … Indeed, in any other context we would immediately recognize such systems as the product of very intelligent engineering. Although some may argue this is a merely an argument from ignorance, we regard it as an inference to the best explanation, given what we know about the powers of intelligent as opposed to strictly natural or material causes.

(Scott Minnich & Stephen Meyer, “Genetic analysis of coordinate flagellar and type III regulatory circuits in pathogenic bacteria,” Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Design & Nature, Rhodes, Greece, M.W. Collins & C.A. Brebbia eds. (Wessex Institute of Technology Press, 2004).)

Put another way, irreducibly complex structures are positive evidence for design because in our experience, they are always derived from intelligence. As Scott Minnich explained in his testimony:

The positive argument is that we know when we find … irreducibly complex systems or information storage and processing systems, from our own experience of cause and effect, that there is an intelligence associated with it. … That’s a uniformitaria[n] deduction from cause and effect that we know from our everyday … experience.”

(Scott A. Minnich, Kitzmiller v. Dover, Nov. 4th AM Testimony, p. 57.)

So where did Judge Jones get the idea that ID is a strictly negative argument? He got it from Ken Miller, who testified: “I have yet to see any explanation, advanced by any adherent of design that basically says, we have found positive evidence for design. The evidence is always negative, and it basically says, if evolution is incorrect, the answer must be design.” Michael Behe directly refuted this testimony — but Judge Jones apparently ignored him:

This argument for design is an entirely positive argument. This is how we recognize design by the purposeful arrangement of parts.

When asked about Miller’s critique of ID, Behe called it “a mischaracterization” and explained his view:

[W]e infer design when we see that parts appear to be arranged for a purpose. The second point is that the strength of the inference, how confident we are in it, is quantitative. The more parts that are arranged, and the more intricately they interact, the stronger is our confidence in design.

Now of course it is true that irreducible complexity is also a negative argument against evolution. In fact, irreducible complexity stands in the special position of being both a negative argument against evolution and a positive argument for design. This makes for a real dichotomy, not a false one. Behe explains this well in the epilogue to Darwin’s Black Box:

[I]rreducibly complex systems such as mousetraps and flagella serve both as negative arguments against gradualistic explanations like Darwin’s and as positive arguments for design. The negative argument is that such interactive systems resist explanation by the tiny steps that a Darwinian path would be expected to take. The positive argument is that their parts appear arranged to serve a purpose, which is exactly how we detect design.”

(Michael Behe, Darwin’s Black Box, Afterward, pgs. 263-264 (Free Press, Reprint), emphasis added.)

Judge Jones focused only on the negative argument. But without the positive argument, we couldn’t infer design.

Errors About the Bacterial Flagellum

On bacterial flagellum, Judge Jones made many scientific errors. He stated:

[I]n the case of the bacterial flagellum, removal of a part may prevent it from acting as a rotary motor. However, Professor Behe excludes, by definition, the possibility that a precursor to the bacterial flagellum functioned not as a rotary motor, but in some other way, for example as a secretory system. … By defining irreducible complexity in the way that he has, Professor Behe attempts to exclude the phenomenon of exaptation by definitional fiat, ignoring as he does so abundant evidence which refutes his argument.

His first sentence is true — but the rest of what he says there is wrong. First, Behe does not exclude from his arguments “exaptation” or indirect routes of evolution where a system or part might be co-opted to acquire some new function during an evolutionary pathway. In fact, Behe addresses this very objection in Darwin’s Black Box:

Even if a system is irreducibly complex (and thus cannot have been produced directly), however, one can not definitively rule out the possibility of an indirect, circuitous route. As the complexity of an interacting system increases, though, the likelihood of such an indirect route drops precipitously. And as the number of unexplained, irreducibly complex biological systems increases, our confidence that Darwin’s criterion of failure has been met skyrockets toward the maximum that science allows. (p. 40)

He further notes that these indirect routes of evolution don’t work because “previous functions make them ill-suited for virtually any new role as part of a complex system.” (p. 66) This last comment goes directly to Judge Jones’s misunderstanding of irreducible complexity (IC). IC relates to the functionality of a collection of parts, not the function (or possible functions) of each individual part. Even if a separate function could be found for a sub-system or sub-part, that would not refute the irreducible complexity of the whole, nor would it demonstrate the evolvability of that entire system. In Darwin’s Black Box (p. 39), Behe defines IC as follows:

In The Origin of Species Darwin stated:

“If it could be demonstrated that any complex organ existed which could not possibly have been formed by numerous, successive, slight modifications, my theory would absolutely break down.”

A system which meets Darwin’s criterion is one which exhibits irreducible complexity. By irreducible complexity I mean a single system composed of several well-matched, interacting parts that contribute to the basic function, wherein the removal of any one of the parts causes the system to effectively cease functioning.

According to Darwin himself, Darwinian evolution requires that a system be functional along each small step of its evolution. A sub-part could be useful outside of the final system, yet the total system would still face many points over its “evolutionary pathway” where it could not remain functional through “numerous, successive, slight modifications.” Thus, Judge Jones mischaracterizes Behe’s argument. I explained this point in more detail at “Do Car Engines Run on Lugnuts? A Response to Ken Miller & Judge Jones’s Straw Tests of Irreducible Complexity for the Bacterial Flagellum.”

Judges Jones is also wrong that the secretory system (called the Type 3 Secretory System, or T3SS), could have served as a precursor to the flagellum. Scott Minnich explained that it’s very different from the flagellum and it would require a great “leap” in complexity for the T3SS to evolve into a flagellum:

Q. Would it be fair to say that if the type three secretory system was found to have preceded the bacterial flagellum, we’d still have difficulty with trying to determine how that one system that functions as a secretory system could then become a separate system that functions as a motor, flagellar motor?

A. Right…having a nano syringe and developing that into a rotary engine, you know, is a big leap.

(Scott Minnich, Nov. 3 Testimony, p. 112.)

Likewise, in his Dover trial “Rebuttal to Reports by Opposing Expert Witnesses,” William Dembski explains:

At best the TTSS [Type-III Secretory System] represents one possible step in the indirect Darwinian evolution of the bacterial flagellum. But that still wouldn’t constitute a solution to the evolution of the bacterial flagellum. What’s needed is a complete evolutionary path and not merely a possible oasis along the way. To claim otherwise is like saying we can travel by foot from Los Angeles to Tokyo because we’ve discovered the Hawaiian Islands. Evolutionary biology needs to do better than that.

Indeed, other scientists outside of the ID movement have said that T3SS was not an evolutionary precursor to the flagellum:

- “Regarding the bacterial flagellum and TTSSs, we must consider three (and only three) possibilities. First, the TTSS came first; second, the Fla system came first; or third, both systems evolved from a common precursor. At present, too little information is available to distinguish between these possibilities with certainty. As is often true in evaluating evolutionary arguments, the investigator must rely on logical deduction and intuition. According to my own intuition and the arguments discussed above, I prefer pathway 2.” (Milton Saier, “Evolution of bacterial type III protein secretion systems,” Trends in Microbiology, 12 (3): 113-15 (March, 2004)

- “One fact in favour of the flagellum-first view is that bacteria would have needed propulsion before they needed T3SSs, which are used to attack cells that evolved later than bacteria. Also, flagella are found in a more diverse range of bacterial species than T3SSs. ‘The most parsimonious explanation is that the T3SS arose later,’ says biochemist Howard Ochman at the University of Arizona in Tucson.” (Dan Jones, “Uncovering the evolution of the bacterial flagellum,” New Scientist (Feb 16, 2008).)

- “Based on patchy taxonomic distribution of the T3SS compared to that of the flagellum, widespread in bacterial phyla, previous phylogenetic analyses proposed that T3SS derived from a flagellar ancestor and spread through lateral gene transfers.” (Sophie S. Abby and Eduardo P.C. Rocha, “An Evolutionary Analysis of the Type III Secretion System,” Evolution 2012 Paper (2012).)

Their argument, in short, is that the T3SS is found in a small subset of gram-negative bacteria that have a symbiotic or parasitic association with eukaryotes. Since eukaryotes evolved over a billion years after bacteria, this suggests that the T3SS arose after eukaryotes. However, flagella are found across the range of bacteria, and the need for chemotaxis and motility (i.e., using the flagellum to find food) precede the need for parasitism. In other words, given the narrow distribution of T3SS-bearing bacteria, and the very wide distribution of bacteria with flagella, phylogenetic analysis would suggest that the flagellum long predates T3SS rather than the reverse. But don’t expect evolutionists to use such normal reasoning when trying to oppose potent arguments for intelligent design.

Now let’s return to the first sentence from Judge Jones, above: “[I]n the case of the bacterial flagellum, removal of a part may prevent it from acting as a rotary motor.” That’s a very important statement and it shows, in fact, that the flagellum is irreducibly complex.

Scott Minnich provided direct evidence for this when he testified about genetic knockout experiments in his own lab at the University of Idaho:

One mutation, one part knock out, it can’t swim. Put that single gene back in we restore motility. Same thing over here. We put, knock out one part, put a good copy of the gene back in, and they can swim. By definition the system is irreducibly complex. We’ve done that with all 35 components of the flagellum, and we get the same effect.” (Scott Minnich Testimony, Day 20, pm session, pp. 107-108)

So Judge Jones was presented with testimony showing that the flagellum could not evolve in the step-by-step manner required by Darwin’s theory. Ken Miller, of course, testified the flagellum could evolve. Fine. At most Judge Jones was presented with evidence of a scientific debate — not evidence that ID had been refuted.

Thus, Judge Jones incorporated errors into his ruling and canonized scientifically false claims. He stated:

Professor Behe has applied the concept of irreducible complexity to only a few select systems: (1) the bacterial flagellum; (2) the blood-clotting cascade; and (3) the immune system. Contrary to Professor Behe’s assertions with respect to these few biochemical systems among the myriad existing in nature, however, Dr. Miller presented evidence, based upon peer-reviewed studies, that they are not in fact irreducibly complex.

However, in his “Response to the Opinion of the Court in Kitzmiller vs Dover Area School District,” Behe writes:

[D]espite my protestations the Court simply accepts Miller’s adulterated definition of irreducible complexity in which a system is not irreducible if you can use one or more of its parts for another purpose, and disregards careful distinctions I made in Darwin’s Black Box. The distinctions can be read in my Court testimony. In short, the Court uncritically accepts strawman arguments.

That’s exactly right. Behe and Minnich rebutted Ken Miller’s claims about the flagellum, Judge Jones ignored that testimony.

For more information on the flagellum, please see the following links:

- “The Bacterial Flagellum: A Motorized Nanomachine“

- “Molecular Machines: Experimental Support for the Design Inference“

- “Spinning Tales About the Bacterial Flagellum“

- Do Car Engines Run on Lugnuts? A Response to Ken Miller & Judge Jones’s Straw Tests of Irreducible Complexity for the Bacterial Flagellum

- “Responding to Criticisms of Irreducible Complexity of the Bacterial Flagellum from the Australian Broadcasting Network“

- “Michael Behe Hasn’t Been Refuted on the Flagellum“

- “Genetic Analysis of Coordinate Flagellar and Type III Regulatory Circuits in Pathogenic Bacteria“

- “Molecular Machines in the Cell“

Errors About the Blood Clotting Cascade

We’ve already seen above that Judge Jones claimed, against Behe, that the blood clotting cascade is “not in fact irreducibly complex.” Jones also wrote:

[W]ith regard to the blood-clotting cascade, Dr. Miller demonstrated that the alleged irreducible complexity of the bloodclotting cascade has been disproven by peer-reviewed studies dating back to 1969, which show that dolphins’ and whales’ blood clots despite missing a part of the cascade, a study that was confirmed by molecular testing in 1998. (1:122-29 (Miller); P-854.17-854.22). Additionally and more recently, scientists published studies showing that in puffer fish, blood clots despite the cascade missing not only one, but three parts. (1:128-29 (Miller)). Accordingly, scientists in peer-reviewed publications have refuted Professor Behe’s predication about the alleged irreducible complexity of the blood-clotting cascade.

Ken Miller had indeed testified that if the blood clotting cascade works without certain parts, then blood clotting isn’t irreducibly complex. But those factors and components cited by Miller were parts that Behe in Darwin’s Black Box expressly did not claim are part of the irreducibly complex core of the blood clotting system. On that, Miller misrepresented Behe’s arguments.

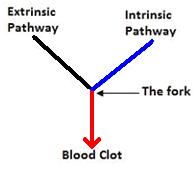

Roughly speaking, there are three “prongs” to the blood-clotting cascade: two pathways that initiate the cascade (the extrinsic and intrinsic pathways) and then the cascade itself, which forms the clot. These prongs are illustrated in the diagram below:

In Darwin’s Black Box, Michael Behe only argues for irreducible complexity for the components after the “fork” (red) in the blood clotting cascade. Behe makes this unmistakably clear on page 86 where he writes: “Leaving aside the system before the fork in the pathway, where some details are less well known, the blood-clotting system fits the definition of irreducible complexity.”

Behe repeated the point in his court testimony:

The relative importance of the two [initiation] pathways in living organisms is still rather murky. Many experiments on blood clotting are hard to do. And I go on to explain why they must be murky. And then I continue on the next slide. Because of that uncertainty, I said, let’s, leaving aside the system before the fork in the pathway, where some details are less well-known, the blood clotting system fits the definition of irreducible complexity. And I noted that the components of the system beyond the fork in the pathway are fibrinogen, prothrombin, Stuart factor, and proaccelerin. So I was focusing on a particular part of the pathway, as I tried to make clear in Darwin’s Black Box. If we could go to the next slide. Those components that I was focusing on are down here at the lower parts of the pathway. And I also circled here, for illustration, the extrinsic pathway. It turns out that the pathway can be activated by either one of two directions. And so I concentrated on the parts that were close to the common point after the fork. So if you could, I think, advance one slide. If you concentrate on those components, a number of those components are ones which have been experimentally knocked out such as fibrinogen, prothrombin, and tissue factor. And if we go to the next slide, I have red arrows pointing to those components. And you see that they all fall in the area of the blood clotting cascade that I was specifically restricting my arguments to. And if you knock out those components, in fact, the blood clotting cascade is broken. So my discussion of irreducible complexity was, I tried to be precise, and my argument, my argument is experimentally supported. [Emphasis added.]

Ken Miller’s would-be response was that some vertebrates — such as the puffer fish or certain cetaceans — lack components of the intrinsic pathway (such as blood clotting factors XI, XII, and XIIa), but their blood still clots. The problem with his argument is that all of the components he cites come before the fork (from the blue “prong”) in the blood clotting cascade. But Behe never claimed that this part of the blood clotting cascade was irreducibly complex. Since, Behe made it clear in Darwin’s Black Box that his argument for irreducible complexity only applied to components after the fork (the red), Miller did not test or refute Behe’s actual arguments.

I wrote about all of this in December 2009 (the links are given below). Ken Miller was given space over in Discover Magazine to reply to me, and in doing so he continued to misrepresent and misquote Behe. For example, in his book Only a Theory Miller claims that Behe cited all the components of the blood clotting cascade both before and after the fork as part of an irreducibly complex system. But he takes Behe’s words out of context: “In the absence of any one of the components, blood does not clot, and the system fails” (p. 86) and “Since each step necessarily requires several parts, not only is the entire blood-clotting cascade irreducibly complex, but so is each step in the pathway.” (p. 87)

But Behe made it very clear in Darwin’s Black Box that the way he defined the “blood-clotting cascade” was to consider only the components after the fork (p. 86):

Leaving aside the system before the fork in the pathway, where some details are less well known, the blood-clotting system fits the definition of irreducible complexity. That is, it is a single system composed of several interacting parts that contribute to the basic function, and where the removal of any one of the parts causes the system effectively to cease functioning. The function of the blood clotting cascade is to form a solid barrier at the right time and place that is able to stop blood flow out of an injured vessel. The components of the system (beyond the fork in the pathway) are fibrinogen, prothrombin, Stuart factor, and proaccelerin. Just as none of the parts of the Foghorn system is used for anything except controlling the fall of the telephone pole, so none of the cascade proteins are used for anything except controlling the formation of a blood clot. Yet in the absence of any one of the components, blood does not clot, and the system fails.

Miller’s entire argument is predicated upon a misrepresentation of Behe. He ought to just retract what he said and move on.

Here are links that explain the story of what happened:

My Initial Salvo:

- “How Kenneth Miller Used Smoke-and-Mirrors to Misrepresent Michael Behe on the Irreducible Complexity of the Blood-Clotting Cascade (Part 1)“

- “How Kenneth Miller Used Smoke-and-Mirrors to Misrepresent Michael Behe on the Irreducible Complexity of the Blood-Clotting Cascade (Part 2)“

- “How Kenneth Miller Used Smoke-and-Mirrors to Misrepresent Michael Behe on the Irreducible Complexity of the Blood-Clotting Cascade (Part 3)“

Miller’s Reply:

- “Smoke and Mirrors, Whales and Lampreys: A Guest Post“

- “Ken Miller’s Guest Post, Part Two“

- “Ken Miller’s Final Guest Post: Looking Forward“

Behe’s Reply to Miller:

My Reply to Miller (and Discover Magazine):

- “Ken Miller’s Only a Theory Misquotes Michael Behe on Irreducible Complexity of the Blood Clotting Cascade“

- “Ken Miller’s Double Standard: Improves His Own Arguments But Won’t Let Michael Behe Do the Same (Updated)“

- “Discover Magazine Fails With Miller’s Failure To Refute Behe“

- “Ken Miller Confuses Weak Assertions of Common Ancestry With Darwinian Evolution of Blood Clotting Cascade“

Ken Miller’s Reply Showing that Miller In Fact Did Not Misrepresent Behe:

- Reply does not exist.

The Origin of New Information

Judge Jones stated that Ken Miller had “pointed to more than three dozen peer-reviewed scientific publications showing the origin of new genetic information by evolutionary processes.” Virtually all of those “publications” mentioned by Judge Jones came from a single paper Miller discussed at trial, a 2003 review article co-authored by Manyuan Long, “The Origin of New Genes: Glimpses from the Young and Old.”

Yet Long et al.‘s article does not even contain the word “information,” much less the phrase “new genetic information.”

As ID proponents have shown, the paper really does not demonstrate unguided evolutionary mechanisms producing new information. For example, I wrote an essay responding to this paper in 2010, “The NCSE, Judge Jones, and Citation Bluffs About the Origin of New Functional Genetic Information.” There I noted:

For the NCSE [National Center for Science Education] / Ken Miller / Judge Jones to claim that there is an explanation or “the origin of new genetic information by evolutionary processes,” they must equivocate on the definitions of both the words “information” and “new.”

Following Miller, Judge Jones never defines what he means by “information.” But the processes cited in Long’s paper rely heavily on gene duplication, a well-established process. That process doesn’t generate any information that is “new.” To actually generate new information you have to have random mutation and/or natural selection acting upon a gene (or a gene duplicate) to produce some new feature of function. As I explain:

[I]t’s easy to duplicate a gene, but the key missing ingredient in many neo-Darwinian explanations of the origin of new genetic information is how a gene duplicate then acquires some new optimized function. Evolutionists have not demonstrated, except in rare cases, that step-wise paths to new function for duplicate genes exist.

In the article, I go through many of the specific examples of “gene evolution” cited by Long et al. and show that “neo-Darwinists do not want to ask the right questions — the hard questions — about the sufficiency of their theory to explain gene evolution. They accept superficial just-so stories in place of detailed, plausibly demonstrated explanations.” These questions — which are never addressed by any of the studies cited in Long et al. — include:

- Question 1: Is there a step-wise adaptive pathway to mutate from A to B, with a selective advantage gained at each small step of the pathway?

- Question 2: If not, are multiple specific mutations ever necessary to gain or improve function?

- Question 3: If so, are such multi-mutation events likely to occur given the available probabilistic resources?

Steve Meyer makes similar observations about this paper in Darwin’s Doubt:

The oft-cited Long paper points to a variety of studies that purport to explain the evolution of various genes. … Upon closer examination, however, none of these papers demonstrate how mutations and natural selection could find truly novel genes or proteins in sequence space in the first place; nor do they show that it is reasonably probable (or plausible) that these mechanisms would do so in the time available. These papers assume the existence of signifi cant amounts of preexisting genetic information (indeed, many whole and unique genes) and then suggest various mechanisms that might have slightly altered or fused these genes together into larger composites. At best, these scenarios “trace” the history of pre-existing genes, rather than explain the origin of the original genes themselves. (pp. 211-212)

He further observes:

[M]ost of the mutational processes that evolutionary biologists invoke in the scenarios cited in the Long essay presuppose significant amounts of preexisting genetic information on preexisting genes or modular sections of DNA or RNA. The Long essay highlights seven main mutational mechanisms at work in the sculpting of new genes: (1) exon shuffling, (2) gene duplication, (3) retropositioning of messenger RNA transcripts, (4) lateral gene transfer, (5) transfer of mobile genetic units or elements, (6) gene fission or fusion, and (7) de novo origination. Yet each of these mechanisms, with the exception of de novo generation, begins with preexisting genes or extensive sections of genetic text. This preexisting functionally specified information is in some cases enough to code for the construction of an entire protein or a distinct protein fold. Moreover, these scenarios not only assume unexplained preexisting sources of biological information, they do so without explaining or even attempting to explain how any of the mechanisms they envision could have solved the combinatorial search problem… (pp. 217-218)

Instead, what Long’s citations provide us with is what Meyer calls a “word salad” of implausible just-so stories:

The assertion of Long and his colleagues about exon shuffling, like many other statements about postulated mutational mechanisms, blurs the distinction between theory and evidence. Despite the authoritative tone of such statements, evolutionary biologists rarely directly observe the mutational processes they envision. Instead, they see patterns of similarities and differences in genes and then attribute them to the processes they postulate. Yet the papers that Long cites offer neither mathematical demonstration, nor experimental evidence, of the power of these mechanisms to produce significant gains in biological information.

In the absence of such demonstrations, evolutionary biologists have taken to offering what one biologist I know calls “word salad” — jargon-laced descriptions of unobserved past events– some possible, perhaps, but none with the demonstrated capacity to generate the information necessary to produce novel forms of life. This genre of evolutionary literature envisions exons being “recruited” and/or “donated” from other genes or from an “unknown source”; it appeals to “extensive refashioning” of genes; it attributes “fortuitous juxtaposition of suitable sequences” to mutations or “fortuitous acquisition” of promoter elements; it assumes that “radical change in the structure” of a gene is due to “rapid, adaptive evolution”; it asserts that “positive selection has played an important role in the evolution” of genes, even in cases when the function of the gene under study (and thus the trait being selected) is completely unknown; it imagines genes being “cobbled together from DNA of no related function (or no function at all)”; it assumes the “creation” of new exons “from a unique noncoding genomic sequence that fortuitously evolved”; it invokes “the chimeric fusion of two genes”; it explains “near-identical” proteins in disparate lineages as “a striking case of convergent evolution”; and when no source material for the evolution of a new gene can be identified, it asserts that “genes emerge and evolve very rapidly, generating copies that bear little similarity to their ancestral precursors” because they are apparently “hypermutable.” Finally, when all else fails, scenarios invoke the “de novo origination” of new genes, as if that phrase — any more than the others just mentioned — constitutes a scientific demonstration of the power of mutational mechanisms to produce significant amounts of new genetic information. (pp. 227-228)

Darwin’s Doubt, my article, and an additional article by David Berlinski and Tyler Hampton each provide detailed analysis of some of the studies cited by Long et al.. Here was my conclusion:

In not a single case did the above papers cited by Long et al. actually explain how new functional information arose. In no case was there an analysis of how natural selection could have favored mutational changes that were shown to be likely along each step of an alleged evolutionary pathway; never was any detailed step-by-step mutational pathway even given. At best, these studies offered vague and ad hoc appeals to duplication, rearrangement, and natural selection — often in a sudden, extreme, and abrupt manner — to form the gene in question. In many cases, natural selection was invoked to allegedly account for changes in the gene, even though the investigators didn’t even know the function of the gene and thereby could not identify the advantage provided by the gene’s function. In no case were calculations performed to assess whether sufficient probabilistic resources existed to produce the asserted mutational events on a reasonable timescale. In some cases, the original genetic material for the genes was unknown, or the studies asserted spontaneous “de novo” origin of genes from previously non-coding DNA. While they readily admitted that “de novo” gene emergence is rare, no attempt was made to assess whether such an unguided mechanism is even remotely plausible on mathematical probabilistic grounds. These papers play the Gene Evolution Game, but never ask the right questions to explain how neo-Darwinian mechanisms create new genetic information.

And Yet It Moves

There’s a famous story — possibly true, possibly not — that after the Inquisition forced Galileo to recant his view that the Earth orbits the Sun, he nonetheless stated, “And yet it [the Earth] moves.” The meaning, of course, is that a government body cannot change the facts of nature by fiat, decree, edict, or order. In his rejoinder to the Dover ruling, “Whether Intelligent Design Is Science: A Response to the Opinion of the Court in Kitzmiller vs Dover Area School District,” Michael Behe says much the same thing. He observes that Judge Jones’s error-filled ruling is

regrettable, but in the end does not impact the realities of biology, which are not amenable to adjudication. On the day after the judge’s opinion, December 21, 2005, as before, the cell is run by amazingly complex, functional machinery that in any other context would immediately be recognized as designed. On December 21, 2005, as before, there are no non-design explanations for the molecular machinery of life, only wishful speculations and Just-So stories.

Behe is exactly right. Judge Jones in his ruling offers a variety of mistaken scientific findings, but that cannot change the facts of nature. In the long view — which understands science to be ultimately self-correcting — there is good reason to hope that the truth of intelligent design will win out. In the short term, however, the Dover ruling spread an immense amount misinformation about the science of ID. Indeed, there are many more scientific problems with the ruling that we just don’t have time or space to address here.

But there is one last problem to mention — something that my colleague Sarah Chaffee alluded to in her recent post on Judge Jones’s activism.

Judge Jones’s claim that “ID’s negative attacks on evolution have been refuted by the scientific community” was, according to him, very important to the logic of his ruling. In Jones’s view, ID’s supposed refutation was “sufficient to preclude a determination that ID is science.” Not only was his claim that ID has been refuted incorrect, but this is abysmally bad as philosophy of science.

An idea can be wrong yet still scientific. In fact, in the history of science such ideas are commonplace. University of Toronto biochemist Larry Moran correctly observes: “Bad science and pseudoscience are science or at least they were accepted as possible scientific explanations until they were discredited. If they weren’t within the realm of science then they could never have been falsified by science.” My co-authors and I similarly wrote in a Montana Law Review article:

University of Kentucky philosopher Bradley Monton observes that being wrong does not necessarily make an idea unscientific. Newtonian physics has been refuted and superseded by Einstein’s theory of relativity. But that does not make Newton’s laws of mechanics “unscientific,” and indeed, physics classes still invariably teach them alongside Einstein’s models. Here it is Judge Jones who proposes the false dichotomy: he wrongly asserts that if a theory is not correct, it cannot be science. But something can be wrong and still be science.

Even so, Behe’s arguments are not wrong at all, as we explained:

On the specific question of Michael Behe and the concept of “irreducible complexity,” it is important to note that while some evolutionists have attacked Behe’s criticisms of the evidence for natural selection, other prominent biochemists have conceded them. Shortly after Behe’s Darwin’s Black Box came out in 1996, biochemist James Shapiro of the University of Chicago acknowledged that “there are no detailed Darwinian accounts for the evolution of any fundamental biochemical or cellular system, only a variety of wishful speculations.” Five years later in a scientific monograph published by Oxford University Press, biochemist Franklin Harold, who rejects ID, admitted, in virtually the same language, “we must concede that there are presently no detailed Darwinian accounts of the evolution of any biochemical or cellular system, only a variety of wishful speculations.” Other scientists have begun to cite Behe’s ideas favorably and seriously in their own scientific publications. What one has here is evidence of a scientific debate, not that Behe’s ideas “have been refuted by the scientific community.”

If Judge Jones is correct that ID’s arguments have been scientifically refuted, that doesn’t mean that ID isn’t science. If anything, it suggests that ID is science. But as we have seen, many of ID’s arguments were not refuted at Dover and they have passed scientific tests. This suggests that ID is not just science, but good science. As for the Dover ruling, the Earth still moves.

Image: Michael Behe.