Evolution

Evolution

A.N. Wilson’s Charles Darwin — A Sense of Déjà Vu

It’s finally here in America — the much-anticipated Darwin biography by A.N. Wilson, the noted English author of fiction and non-fiction. The nicely produced illustrated plates (some in color) and its sheer girth (438 pages) greeted this anxious reader with the sense that something special awaited. To be sure, stylistically, Charles Darwin: Victorian Mythmaker does not disappoint. The writing is clear and crisp as it carries the reader along the remarkable journey of this remarkable man. While leaving the science to others, this review will focus on historical and historiographical issues with the book.

Wilson sees two Darwins: the brilliant and indefatigable naturalist, and the murky, protective, self-absorbed speculative theorist. I do not disagree with any of this. The essential thesis is this:

It is this book’s contention that Darwinism succeeded for precisely the reason that so many critics of religions think that religion succeeded. Darwin offered to the emergent Victorian middle class a consolation myth. He told them that all their getting and spending, all their neglect of their own poor huddled masses, all their greed and selfishness was in fact natural. It was the way things were. The whole of nature, arising from primeval slime and evolving through its various animal forms from amoebas to the higher primates, was on a journey of improvement, moving onwards and upwards, from barnacles to shrimps, from fish to fowl, from orang-outangs to silk-hatted Members of Parliament and leaders of British industry. It was all happening without the interference or tiresome conscience-pricking of the Almighty (17-18).

Wilson goes on to write that Darwin “was a self-mythologizer, a man who wanted to represent himself, when the time was ripe, as the pioneer evolutionist” (52). This grew into an insatiable passion evidenced even in his private notes where he refers to “my theory” (156). Far from this theory being developed slowly through the patient, objective investigation of nature itself, Darwin’s brief but transformative stint as a medical student at the University of Edinburgh under the influence of the free-thinking Plinian Society and his materialist mentor Robert Edmond Grant gave the impressionable teenager the template for a worldview that would last throughout his life. So single-minded was Darwin in pursuit of “my theory” that Wilson argues Darwin abandoned science in favor of propaganda (292). But because evolution (then known as transmutation) was “in the air,” Darwin launched a systematic campaign of deliberate suppression of his predecessors largely by refusing to acknowledge them.

I again concur. The problem is I’ve heard all this before. Gertrude Himmelfarb covered the evolution “in the air” idea well in her Darwin and the Darwinian Revolution (1959, rev. ed., 1962). Darwin’s Edinburgh influences have been brilliantly exposed in Adrian Desmond and James Moore’s Darwin: The Life of a Tormented Evolutionist (1991), and Benjamin Wiker covers Wilson’s central theme in The Darwin Myth (2009). Neither Himmelfarb nor Wiker is cited in Wilson’s bibliography, and Desmond and Moore’s work is referenced much too sparingly.

But my uneasy sense of déjà vu turned to dismay when I read Wilson’s claim that Darwin did more than merely suppress his predecessors, he actually stole ideas from Edward Byth’s proto-theory of natural selection, published in two essays appearing in the Magazine of Nature History in 1835 and 1837. Wilson claims some mysteriously missing pages in Darwin’s notebooks prove it. The problem is, these have long been recovered and are readily available in Charles Darwin’s Notebooks, 1836-1844 (1987). Historians have since examined these discovered pages and have concluded that there is no substantiation to the charge of intellectual thievery on the part of Darwin, an accusation first issued by Loren Eiseley in 1959 before the lost pages were found. It is puzzling that Wilson resurrected such a baseless charge, especially when the countervailing evidence sat right under his nose with the published Notebooks he cites in his biography.

As if this weren’t enough, there are a multitude of simple factual errors in the book. For example, Darwin’s first grandchild did not die in childbirth. Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (1844) did not “scoop” Darwin. Herbert Spencer did not suggest Darwin adopt the phrase “survival of the fittest.” The alleged “July 1” meeting of the Linnean Society was not cancelled because of Society President Robert Brown’s death ten days later! Alfred Russel Wallace’s theory of natural selection was not “all but identical” to Darwin’s. The list could go on.

Although I began Wilson’s biography expecting something special, that anticipation soon faded amidst a plethora of problems: familiar ideas served up without reference (“Physician, heal thyself”?), misattributed quotes, numerous factual errors, and analyses that vacillated between the sad resurrection of an old falsehood to the bland assessment that Darwin’s distinctive contribution was to make nature impersonal. Did he really mean that or did he mean purposeless? The two are not synonymous. My closing impression is that Wilson padded his bibliography and didn’t really look at most of what he cites. How else could he make that embarrassing Blyth blunder? And as for deliberate suppression, how could Wilson reference two books by Himmelfarb on the Victorians and miss her noteworthy (some say notorious) Darwin study? Odd, very odd. Those who wish to know more can read my complete assessment here. In any case, this biography is not recommended.

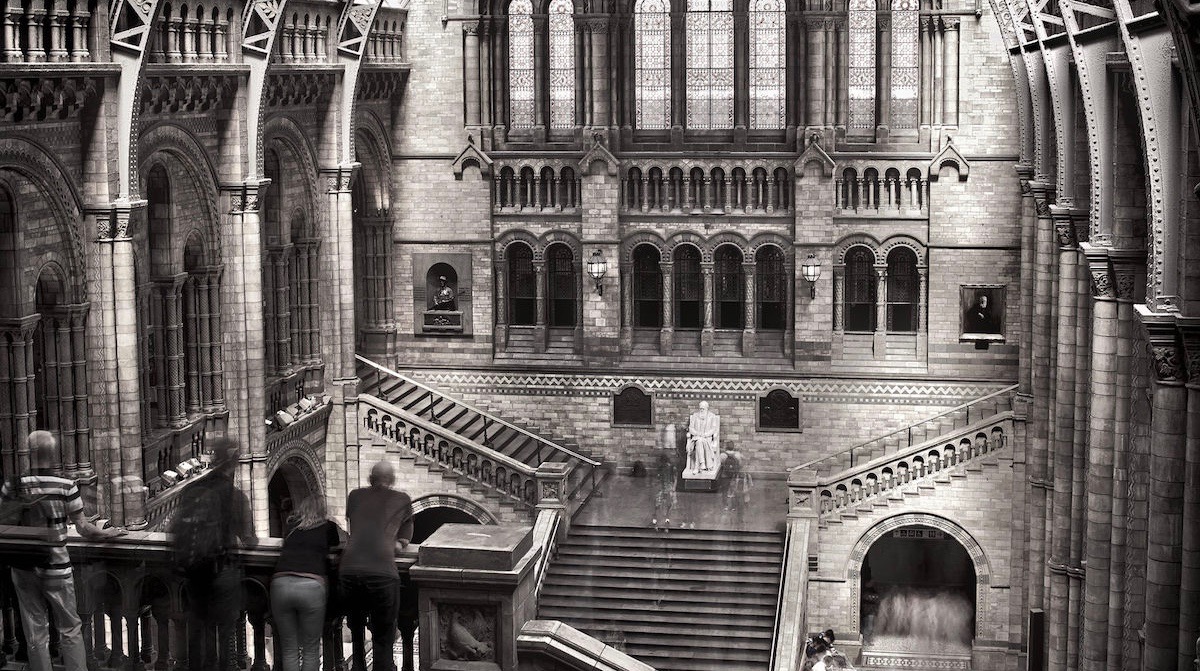

Photo: Visitors admire the iconic Darwin statue at London’s Natural History Museum, by Thomas Fabian, via Flickr.