Intelligent Design

Intelligent Design

Näsvall et al. Demonstrates the Effectiveness of Intelligent Design

This is a tale of five documents. To help keep them straight I will introduce the documents here, followed by a shorthand designation for each. The many human actors will remain in the shadows as much as possible so as to avoid introducing personality issues.

- Mike Behe’s new book, Darwin Devolves. (Behe’s book)

- Review article in the journal Science, “A biochemist’s crusade to overturn evolution misrepresents theory and ignores evidence,” by Lents, Swamidass, and Lenski. (Review)

- “Real-Time Evolution of New Genes by Innovation, Amplification, and Divergence,” by Joakim Näsvall et al., Science 338:384, 2012. (Näsvall et al.)

- For a brief overview see “New Genes Arise via Innovation, Amplification, Divergence,” by Andersson and Näsvall,” Microbe 8(4):166-179, 2013. (Overview)

- “Reductive evolution can prevent populations from taking simple adaptive paths to high fitness” Gauger et al., BIO-Complexity 2010(2):1-9. (Our paper)

The dispute started when the review in Science proposed the 2012 article by Näsvall et al. as evidence against Behe’s book.

A short article at Evolution News then criticized Näsvall et al. by quoting an excerpt from the book Heretic. This excerpt argued that Näsvall’s carefully controlled experiment didn’t supply proof that unguided evolution could produce entirely new functions. As I explain below, I agree with this basic point. However, the excerpt also included a discussion of our paper on reductive evolution, highlighting it as showing the limits of evolutionary processes. That is fine on its own. Nevertheless, in the context of the Evolution News article, this second part of the excerpt might be misleading. Some people might think our article was intended to refute Näsvall et al. As I will explain shortly, it wasn’t, because it used different methodology. Then I’d like to add to the argument about why Näsvall et al. does not refute Mike Behe’s book.

A Different Method, a Different Purpose

Regarding our paper on reductive evolution: Our experiments used a completely different method and had a different purpose from Näsvall et al. The focus of our paper was on the cost of gene expression, the cost of carrying many copies of the same gene and making lots of protein. The reason? In the early stages of gene recruitment, when a nascent protein activity was just beginning, it would probably be very weak. Many copies of the protein would be needed to have a beneficial effect. But there is a cost to carrying extra genes and expressing them. We wanted to examine that trade-off.

Our experiments were done using a high copy number plasmid with lots of non-functional protein being expressed from a few trp genes. In fact, the trp genes on that plasmid were probably making more product than any other gene in the cell, and all of it was non-functional due to two inactivating mutations. So any cell that stopped making the useless protein from those trp genes had an immediate growth advantage. On the other hand, if the cells reverted the two inactivating mutations, they would recover full function. Which thing happened? It isn’t hard to predict. Cells have no foresight and mutation happens at random. Hitting a much bigger target (there are potentially thousands of ways to disrupt a trp gene) is much easier than reverting one single base out of the entire 4.4 Mb genome in E. coli. As a result, in our experiments, before long the entire culture was full of cells that no longer expressed the broken trp genes, or the genes had been deleted. This is not the same sort of experiment as Näsvall et al. at all. We were not trying for exaptation. Initially we just wanted to figure out why cells weren’t taking what seemed to be a simple two-step path to function. The answer was the cost of gene expression.

With that out of the way, I’d like to explain more fully why the 2012 article by Näsvall et al. doesn’t refute Behe’s book.

Näsvall’s Designed Exaptation Scenario Worked

Näsvall’s paper is a beautiful study that demonstrates nothing terribly surprising. Under engineered circumstances, exactly the kind of thing that evolutionary biologists have said could happen, did happen — namely, the recruitment of an enzyme to a new function by gene duplication. The process is also called cooption or exaptation. There you go. Lots of words for the same general idea. There are other ways of discussing exaptation — tinkering is another word. Only two caveats: The Näsvall results were all engineered, and the function wasn’t new.

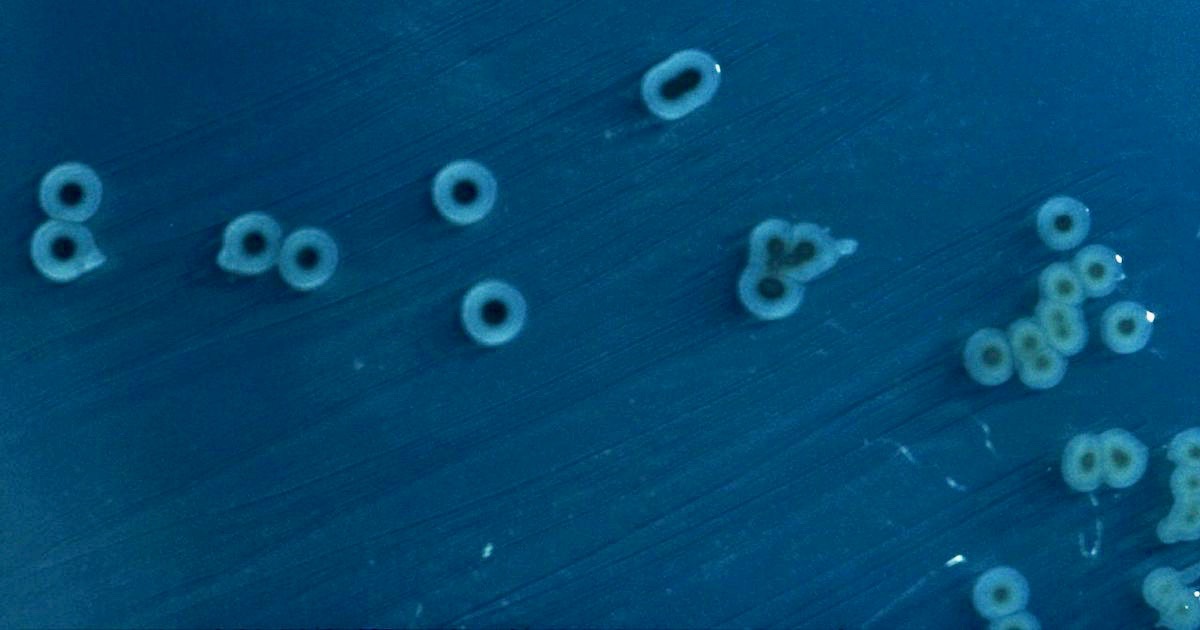

The story: Näsvall et al. created a gene that encoded an enzyme that was able to carry out two functions, but very poorly. They placed that gene in a strain of Salmonella that lacked the genes for those functions. Then they cultured the bacteria under conditions where they needed to carry out those functions to grow. Guess what? The bacteria duplicated the genes so as to make more of the poorly functioning enzymes. Over time, the genes acquired mutations (remember, we are talking about a lot of bacteria) and the ones that helped the most gave the best growth rate, and… after thousands of generations they had evolved separate enzymes for each function — meaning not that they had evolved new enzymes, but that they had divided up the pre-existing dual-functional gene into two genes.

This is not surprising. The experiment was set up to succeed: The starting point was a gene whose protein product had both desired activities already, the original enzymes shared the same structure and were believed to share a common origin, they had overlapping function, and it had already been shown that recruitment would work in one direction. That pretty much meant it was a best case scenario, and very likely to work. They also inserted the starting gene into a plasmid that duplicated easily, to increase the chances of actually seeing something happen. Take home lesson: It worked because it was designed to work.

Näsvall’s scenario is a bit like teeing up the engineered genes in the appropriate strains and then thwacking them down the fairway. After all, they had engineered both activities into one gene, placed them in just the right environment, and made sure both activities were available from the start. Out in the rough, away from the fairway, with no specially prepared genes in just the right location, and no protected habitat with just the right medium to drive things along, who knows? (Imagine a Berlinski shrug.)

Behe Discusses Exaptation in His Book

The review of Behe’s book said rather forcefully that Behe did not discuss exaptation. This statement is false, as others have shown. Instead of “exaptation,” Behe simply used other words such as “tinkering” and “duplication.” I did a search using “duplication” and bingo, I found lots of discussion of recruitment (aka exaptation), much of it skeptical, but not all. Behe says concerning exaptation:

Everyone, including me, thought we knew a lot more than we did. Still, no one should now make the opposite mistake and leap to the conclusion that no development of protein function at all can occur by a classical Darwinian mechanism. As I mentioned in Chapter 6, a cichlid rhodopsin has apparently switched multiple times between two forms sensitive to different wavelengths of light,4 and a recent study of Andean wrens discovered a point mutation that caused its hemoglobin to bind oxygen more strongly.5 Those and similar simple examples are straightforward. However, whenever multiple amino acid substitutions or other mutations were needed to confer a substantially different activity on a duplicated protein, it can no longer be blithely assumed that the transition was navigated by Darwinian evolutionary processes. Some may have been, but many others not.

Behe Has Dealt with Näsvall et al., Repeatedly

Despite Behe’s engagement on the topic, the Science reviewers listed a number of articles they felt Behe should have addressed concerning exaptation in addition to what he did say. Among the papers the reviewers listed was Näsvall et al.1 This is ironic, as we shall see. Even though Behe discussed cases of genuine, non-engineered exaptation in his book (as mentioned above) that was not enough for the reviewers. They told him he should have used an artificially designed system like Näsvall et al.’s to demonstrate unguided evolution.

You know the expression from carpentry, “Measure twice, cut once”? Well, I am trying out a new one: “Tell them twice, so they’ll hear you once.” The Science reviewers felt Behe should have addressed Näsvall et al. Yet Behe already discussed Näsvall et al. when the paper first came out. At that time, he explained:

Although the printed paper itself and an accompanying commentary by Elizabeth Pennisi paint the results as an advance in understanding evolution, that’s so only if evolution has eyes and a mind like a kid solving a maze…. Reading a brief part of the supplemental Materials and Methods section, entitled “Selection for bifunctional HisA mutants,” is enough to see the absurdity of taking the results as a model for undirected Darwinian evolution[:]…

- They deleted an enzyme that previous work showed could likely be replaced.

- They added the necessary nutrient histidine because previous work showed that mutations conferring an ability to make tryptophan destroyed the ability to make histidine.

- The added histidine would have shut off production of the protein, so they removed the genetic control element to keep it in production.

- Later, once they found mutations to produce tryptophan, they removed histidine from the medium to encourage the production of mutations restoring histidine synthesis.

In other words, the paper described an intelligently designed experiment that demonstrated gene duplication could happen, if everything was arranged just right.

Behe is still discussing Näsvall et al. in this latest controversy. Yet his critics keep coming back, saying he hasn’t responded. He has responded, just not the way they want. In Science, the reviewers say, “Andersson et al. showed that new functions can rapidly evolve in a suitable environment. Behe acknowledges none of these studies, declaring an absence of evidence for the role of duplications in innovation.” 2 Well, that statement is flat-out untrue. The description of the results in Näsvall (aka Andersson) et al. is highly misleading. No new functions evolved, they were merely partitioned to separate proteins. Second, the phrase “a suitable environment” hides quite a lot. Just look up above for a description of all the special preparations that were made. Third, Behe acknowledges these studies, he just denies that they show what Lents et al. claim for them. Näsvall et al. cannot tell us what exaptation can do in the rough. For that we would need other studies that do not rely on investigator manipulation — such as Richard Lenski’s long-term evolutionary experiments (LTEEs).

That’s why it is so odd that Lenski at least does not acknowledge the difference between his work, where bacteria are grown for 60,000 generations without experimental interference, and Näsvall et al.’s work, where the cells were prepared and set up for a particular evolutionary success in every way possible. Sure, the mutations were random in both cases, but the conditions that controlled outcome were vastly different.

In his comments here, “Train Wreck of a Review: A Response to Lenski et al. in Science,” Behe’s frustration shows:

As I write in Darwin Devolves, in his own terrific 60,000-generation evolution project, Lenski discovered the devastation wreaked by unguided, random mutation plus selection.

Let me emphasize: in reviewing a book expressly advocating intelligent design, Lenski et al. can’t seem to distinguish between experiments where investigators keep their hands off and those where investigators actively manipulate a system. Perhaps they can’t see the difference.

Näsvall et al. Demonstrates the Effectiveness of Intelligent Design

To summarize, Näsvall et al.’s work does not invalidate Behe’s book. On the contrary, the paper shows exaptation occurring under the guidance of an intelligent agent.

Näsvall et al. were trying for exaptation, and they set it up beautifully. Straight down the fairway. I do wonder what would have happened if they just left the ball on the tee.

Notes:

- I must say, this is a strategy that can be abused. The scientific literature is enormous, and very few have a comprehensive grasp. It is always possible to find more papers with which to play Gotcha. “But what about this? Have you answered this one?” I hope they do not play that game.

- Näsvall is the first author on the paper they refer to as Andersson et al. The standard way to reference is by the first author. The citations Näsvall et al. and Andersson et al. refer to the same paper. There is, however, an Andersson et al. paper from 2013, listed as #4 at the top of this article, offering an overview.

Photo: Salmonella enterica, by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.